Some costly NFTs grant membership to exclusive groups that enjoy such benefits as yacht parties, but the asset class is vulnerable to speculation and its complexities put off regular investors

Earlier this month, the rap impresario Eminem spent 123.45 units of ether cryptocurrency — worth more than US$450,000 at the time — on an image of an ape that looks kind of like him. Earlier this week, Madonna signaled that she, too, might be interested in splurging on an ape cartoon.

Sure, celebrities often crave the notoriety that comes with head-scratching spending sprees, but it is still fair to ask: Ape caricatures? What on earth are they thinking?

The likely answer might help address the widespread puzzlement about the popularity of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) — those emblems of digital cachet whose collectors are often likened to connoisseurs of fine art or collectibles like baseball cards.

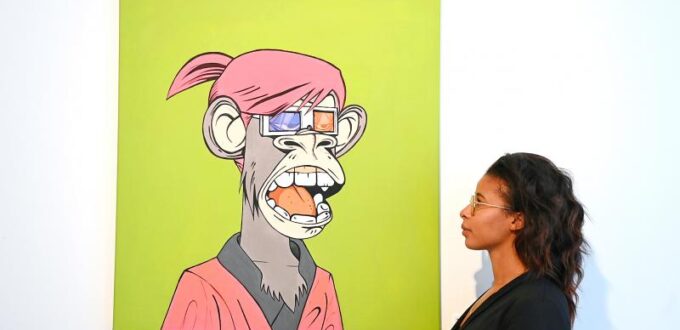

Photo: EPA-EFE

While there are indeed similarities between the worlds of art, collectibles and NFTs, there are also important differences that are crucial to understanding both the appeal and the risks. Strange as they may seem at first glance, NFTs provide owners with psychic and practical benefits that are not obvious to others.

The apes are part of a 10,000-piece cartoon series called the Bored Ape Yacht Club, and the whole series is available on the Internet for anyone to access. What Eminem really bought is an NFT, a database entry connected to his image that is stored on the ethereum blockchain — effectively, a cryptographic record declaring him the owner, a kind of digital deed.

Eminem could presumably get many artists to make ape images for less money and in a form that would give him more control over how the image is used. After all, there is nothing to stop anybody from downloading Eminem’s Bored Ape

So why buy one? These particular images are having a moment in the cultural zeitgeist, with writeups in The New Yorker and Rolling Stone, but there is more to it than that.

Owning a Bored Ape NFT grants access to an online community of holders, as well as limited-edition merchandise and a range of physical and virtual events. With the cheapest Bored Ape on the market priced at about US$240,000, owners form an exclusive and self-selecting club.

This is one reason the wealthy have always collected art. Ownership provides access to a community of similarly endowed owners and sometimes to career-enhancing status symbols like membership on museum boards.

NFTs make the process of forming a community around artworks simpler: All a would-be community-builder needs to do is create an online chat room and control access cryptographically, so people can enter it only if they possess a cryptowallet — an app for storing digital assets like bitcoin or ether — that holds the appropriate NFT. (The Bored Apes’ creators did not stop with virtual connectedness. In November last year, they organized a literal yacht party for holders.)

Bored Ape NFTs also give people commercial rights to their apes for as long as they hold the associated tokens. That means that if Eminem wanted to use his Bored Ape in a music video or concert promotion, he would be welcome to, whereas somebody else who downloads the image would not.

This sort of application is not far-fetched: Another Bored Ape holder has started putting together a virtual Ape band with backing from Universal Music Group, something like a 2020s Gorillaz.

The more people like Eminem acquire Bored Ape NFTs, the more publicity the project gets and the more valuable it becomes to be in the associated network. That drives up the prices of the tokens themselves, to the benefit of current holders.

Moreover, many NFTs are programmed so that their original creators earn royalties each time the NFT is resold, which means the more big sales an NFT collection has, the more money the creators have to invest in providing additional benefits to holders.

There are dangers, too. Some NFT categories catch on, but most do not. As with any new asset class, speculators distort the NFT market, and crypto’s inherent anonymity makes it easy to run pump-and-dump or Ponzi schemes. As with cryptocurrency, the regulatory frameworks around NFT creation, ownership and trading have not been sorted out yet.

On top of that, digital assets like NFTs face an unusual existential challenge. When somebody buys a painting, she owns a physical object that can adorn a wall and — excepting special circumstances like provenance fights — nobody can take it away.

With most NFTs, by contrast, the images live on file servers; if those servers break down or get replaced, the images can get lost. The tokens themselves can in a sense become disconnected and effectively worthless if crypto platforms choose to stop recognizing them. There are efforts under way to address this by building more robust, distributed ways to host and access NFTs, including encoding the entire assets onto the blockchain.

Equally important to solve are issues of access. Crypto markets are notoriously difficult to get into and while most NFTs are not as expensive as Bored Apes, especially with transaction costs even the cheapest ones can still be beyond the budgets of ordinary collectors like me.

If the NFT market is to go truly mainstream, buying them would have to be as simple and cheap as picking up a pack of baseball or Pokemon cards.

As the NFT market expands, many NFTs would serve less as fine art or investment assets, and more as collectibles that anchor communities of like-minded enthusiasts. While some rare collectibles sell for big money, most of them never qualify for auctions at Sotheby’s or even a spot on Pawn Stars. That means NFTs can be appropriate for Eminem, who can afford to lose US$450,000, while at the same time being accessible to people for whom Bored Apes are way out of range.

Another advantage of digital assets is that pretty much anyone can make them. Creators can launch their own NFT projects around their favorite animals, vegetables, or minerals — and that means at least in principle there can be an NFT community for everyone.

Scott Duke Kominers is the MBA class of 1960 associate professor of business Administration at Harvard Business School, and a faculty affiliate of the Harvard Department of Economics.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Comments will be moderated. Keep comments relevant to the article. Remarks containing abusive and obscene language, personal attacks of any kind or promotion will be removed and the user banned. Final decision will be at the discretion of the Taipei Times.

No Comments Yet