Altogether, it was quite a plunge for Jacob Runyan and Chase Cominsky, two stars of the professional fishing world. In a matter of weeks they went from nearly sealing top team honors to facing prison time.

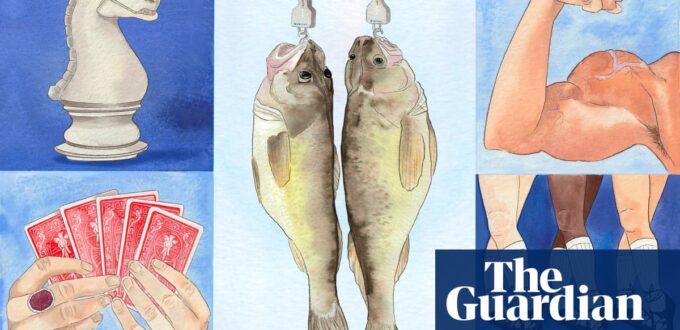

Their alleged crime? Filling the insides of their five Lake Erie walleyes with stones and supermarket filets at a north-east Ohio angling tournament. The tournament director, Jason Fischer, sounded the alarm after gutting their catch, screaming: “We got weights in fish!” The alleged perpetrators could only sit sheepishly behind the cops who had come to arrest them as an angry spectator mob closed in.

In October, a grand jury indicted Runyan and Cominsky on felony charges for cheating, attempted grand theft, possessing criminal tools and misdemeanor charges of unlawfully owning wild animals. If convicted, they could spend up to a year in prison. They quickly posted bail after entering not-guilty pleas. But that didn’t stop Fischer from pronouncing Fishgate “the most disgusting and dishonest act that the fishing world has seen in live time”.

In another year their alleged stunt would be an all-timer. But it turns out theirs was just an appetizer. The sports world in 2022 was staggered by one cheating scandal after another – suggesting that there is an endemic problem in professional competition.

Most of these cheating cases have undermined trust in sport, with accusations flying wildly and contempt for fellow competitors. But few offer much in the way of proof, and suspected parties have maintained their innocence.

Hans Niemann, a 19-year-old American grandmaster, saw world No 1 Magnus Carlsen withdraw from a major tournament match for non-health reasons – a stunning concession that amounted to an act of protest. Two weeks later, Carlsen resigned from an online tournament two moves into a rematch with Niemann. In between, a third prime chess player jokingly posited that Niemann’s mentor was transmitting him computer-assisted moves through vibrating anal beads, and the facetious suggestion caught on like wildfire.

The world’s oldest and largest competitive Irish dancing organization was forced to launch a major investigation after it received allegations that top teachers were purported to have rigged competitions for their students. Some were accused of trying to fix competitions. In another case, a dance teacher was accused of having traded sexual favors for higher scores.

The alleged deceptions didn’t stop there: the No 1 ranked doubles team in professional cornhole (the bar and backyard bean bag toss game) came under fire for using undersized pillows (judges found the duo were using undersized bags, but so were their competitors). A former Survivor contestant claimed he had been hustled out of a jackpot in a high stakes Texas hold ’em game by an Instagram influencer rookie player who might have had help from a vibrating ring. Her coach said she had gotten lucky while confusing the hands she had played.

THIS JUST HAPPENED…@RobbiJadeLew vs @GmanPoker in one of the strangest poker hands you've ever seen

Tune in now for SUPER HIGH STAKES $100/200/400: https://t.co/VcpZNMUTi4 pic.twitter.com/iGppl6l9aa

— Hustler Casino Live (@HCLPokerShow) September 30, 2022

n”,”url”:”https://twitter.com/HCLPokerShow/status/1575668051948687360″,”id”:”1575668051948687360″,”hasMedia”:false,”role”:”inline”,”isThirdPartyTracking”:false,”source”:”Twitter”,”elementId”:”7883ec36-ef4b-426b-a62a-db3a10467bc6″}}”>

Even this year’s Miss USA competition ended in a walk-off protest of the pageant; some contestants believed Miss Texas’s win was pre-determined by event organizers.

Typically, these kinds of scandals come in single file; the marquee college athletics program toppled by illegal payouts, the hero record-setter who was juicing the whole time.. But in 2022, there wasn’t even time to catch a breath. You didn’t just have Nascar, the cradle of outlaw culture, disqualifying the top two finishers of one race for cheating, you had the House oversight committee finding evidence of Dan Snyder skimming profits from his fellow NFL team owners.

Those controversies, says Megan Bartlett, founder of the Center for Healing and Justice through Sport, put fresh focus on “the contradictions between humanity and sports”.

There were plenty of other cases that hadat least the whiff of unfair play. This was the year the World Cup was played in Qatar, long alleged to have clinched the rights through bribery. Max Verstappen repeated as Formula One champion despite his Red Bull Racing team exceeding the 2022 cost cap and the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile declaring his 2021 crown the consequence of a “human error” officiating call. Major League Baseball’s Houston Astros won the World Series with five carryovers from the same group that was outed for cheating their way to the title five years earlier. At a pre-qualifying event on the Korn Ferry Tour, a hothouse that feeds the PGA Tour, a 35-year-old player who had made the cut was disqualified for shaving strokes off his game. (Initially, he had partially attributed his breakthrough round to a lucky bounce off a wild turkey.)

All of it was enough to overshadow a major gambling scandal in which cheating was proven and punishment was handed out: the NFL issuing a year-long suspension to the Atlanta Falcons receiver Calvin Ridley for laying $1,500 on a Falcons win, a wager that cost him $11m in salary.

Smaller competitions once regulated through self-policing have become the focus of television cameras and sponsorship, giving competitors a motive to try to gain an edge. In his book The Edge: The War against Cheating and Corruption in the Cutthroat World of Elite Sports, Roger Pielke Jr makes a case for cheating as an inherently human trait. “And then when the stakes are so much higher – people’s careers, global visibility, big-money contracts – the incentives are all there,” says Pielke, an environmental studies professor at the University of Colorado. “Mix in core governance of competition, and it’s a pretty fertile Petri dish for all the things that you just listed off – which is quite a list.”

Cheating isn’t just part of competition. It’s the other side of the coin. Elite sports in particular have long been premised on the idea of gamesmanship, or how far a competitor can bend the rules. It’s that spirit of innovation that animates sign stealing in baseball and pushes engineering innovations in auto racing. And while it’s expected that the best competitors would occasionally cross the line, it’s strange that so many would pick this year to do it.

But consider the money at stake. Global sport is an estimated $500bn industry, and even ostensibly minor leagues dangle major spoils. Niemann, the teen chess master, was playing for a $350,000 payday. Ace cornhole players can make $250,000 annually. In the pro fishing world, expensive trucks and boats are common giveaways. Last season Runyan and Cominsky split more than $300,000 in competition earnings; top team honors would have netted a $29,000 bonus in 2022. “We’ve created this system where those who make it to the top are compensated in a way that is so disproportionate to the rest of the world that you’re bound to run into these scandals,” says Bartlett.

What’s more, there are fewer taboos around profiting. College amateurs are now free to earn money off their names, images and likenesses. Cryptocurrency became a major sponsor of professional sports – and then, a major liability for the NBA’s Miami Heat and arena naming rights deal with the embattled firm FTX. Sports that were once staunchly anti-gambling not only promote betting lines and sports books with games, but at games.

Since a 2018 supreme court ruling opened the door for states to legalize sports betting, the NFL signed DraftKings, FanDuel and Caesars to multiyear pacts worth just under $1bn combined. Last year Washington DC’s Capital One Arena, home to the NBA’s Wizards and NHL’s Capitals, became the first major US athletics venue to feature a sports book. “I work at a university that signed one of the first contracts with a gambling company,” Pielke says. “You can argue it both ways. One is we’re taking stuff out of the shadows and putting some light on it so it can be regulated. On the other hand, where do you draw the line? Sport is not a place that’s carved out and has its own rules. It’s a pretty good reflection of all that’s good and bad in everything we do.”

All of this trickles down. When the object of competition is all about being elite, it changes the game for young players. It puts incredible pressure on them to when the focus was once on having fun or honing a lifetime hobby. Where public money once went toward pools and parks that fostered community sports, now it’s parents who invest thousands into elite club teams in hopes that it might yield athletic scholarships or professional careers for their kids. An early focus on the zero-sum game can seed the impetus to cheat later in life.

For others, sports are a convenient political tool: take, for example, the case of the swimmer Lia Thomas. Thomas, who initially competed in men’s races, joined the University of Pennsylvania’s women’s swim team after undergoing hormone therapy treatment for over three years, the requirement for such a switch. She was publicly branded a cheater while excelling in the pool and winning an NCAA title – the first of any kind by a transgender athlete. Says Bartlett: “If we’re arguing that sport is a human right and if we’re allowing the complication of competitive advantage to get in the way of that, then how do you find fairness there?”

Most ironic: those same people decrying Thomas couldn’t care less about throwing the book at competitors who break actual rules. Niemann, though cleared of wrongdoing in the $350,000 chess tournament, still competes in live matches even after a 72-page Chess.com report found the teen had probably cheated in more than 100 online games. (Though Niemann is suing his rival Carlsen and others for $100m in hopes of clearing his name, he has admitted to cheating in prior online matches to boost his streaming numbers.)

The cornhole beanbag controversy was ruled unintentional. The poker scandal didn’t warrant an investigation. The chair of the Irish dancing body at the center of that cheating scandal recently survived a no-confidence vote. The suspense over the Miss USA pageant president’s fate was quickly overtaken by news of her husband, the pageant’s VP, being forced to step down for sexually harassing models. “We did have four years of unchecked consequences,” says Bartlett, alluding to the Trump presidency. “Sports are right at the top end of power and privilege. If the incentives continue to be so massive and the punishments so small, what’s going to stop it?”

With prize money mostly derived from entry fees, professional fishing is bound by the honor code. It’s only because their game is state-regulated that fishermen have the law to back them up.

Runyan and Cominsky, of all people, should have known better. At the very same event in 2021, the duo were disqualified after one of them failed a polygraph – an integrity failsafe that provides some idea of how seriously fishermen take their sport.

Even if Runyan and Cominsky only lose their licenses and never fish again, they figure to go down as footnotes in an era when vice became virtue and scammers became kings. This is simply the world we live in now. At best, says Bartlett, parents who are exhausted with scammer culture seeping into sports could spend their money on alternative entertainment for the family. But what happens when kids still want to play? “We’re trying to encourage a more holistic view, to change the mindset – sport is something that helps kids become good humans. But that’s a big leap when you’re operating in a system that only rewards winning.”

Considerable effort has been made over the decades to curb cheats in all forms, from random drug testing to computer-assisted officiating. But in the end, officials are still chasing motivated individuals looking for any edge their rivals won’t see coming. For Runyan and Cominsky, the alleged con was as simple as stuffing fish inside other fish.

As long as fans can’t curb the expectation for historic races, thrilling games and otherwise awe-inspiring feats, the urge to cheat will overwhelm and the stunts will only get bolder. Fraud is just part of the spectacle now, and there’s no more suspending disbelief. “I’m kind of a realist,” Pielke says. “You can enjoy competition and recognize it’s an imperfect human institution at the same time.”

No Comments Yet